The awkward and sluggish looking ocean sunfish, otherwise known as Mola mola, may actually be a little more impressive than you previously thought. With swimming speeds comparable to pelagic sharks, fins with propulsion force analogous to flipper beats of penguins, and deep-diving abilities similar to humpback whales, the ocean sunfish is actually a pretty remarkable fish. While much is left to learn about the biology, physiology, and ecology of this bizarre creature, a new study reveals some insight into their foraging behavior.

While out on a diving or tourism boat in Monterey Bay, it is almost a daily site to see a sunfish“laying out” on the surface. There are a few theories behind this sunbathing behavior, a popular one being that it is an invitation for birds and cleaner fish to clear off some of the sunfish’s parasites (which they are loaded with). Others assume these fish are simply lazy and inactive. However, a recent study suggests that this sunbathing behavior may play an important role in thermal body regulation between deep foraging dives.

Very recently, a group of researchers from the University of Tokyo strapped several sunfish with accelerometers and cameras with lights to record the sunfish foraging excursions to the deep. They found that the fish spend the majority of their time between 100-200m, and feed mostly on siphonophores (a class of marine animals in the order of Hydrozoa) between 50-200 meters. They also attached thermometers to the sunfish to study changes in the fish’s body temperature during these foraging dives. They found that there is a direct relationship between the amount of time the fish spent at cold, deep depths and the post-dive surface interval. After measuring body temperatures from sunfish during deep dives and surface intervals, they found that the heat-transfer from the surrounding water increased by 3-7 times the amount when the sunfish was warming than when it was cooling. It appears that these fish posses some physiological mechanism(s) for quick increases in body temperature that may allow them to spend more time at deeper, colder depths.

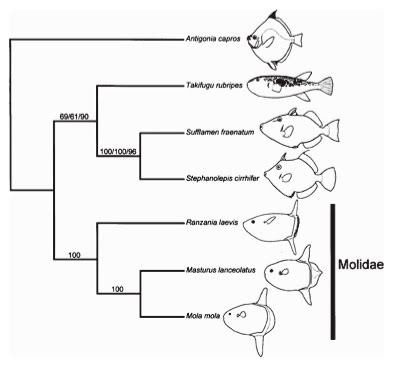

This may also give some insight as to how the sunfish managed to develop into such an oddly shaped animal. Although it looks like a prehistoric creature that somehow escaped the pressures of evolution (and lost its tail along the way), the sunfish is actually a very modern, and one might even dare to say, sophisticated fish. Ocean sunfish are closely related to pufferfish and boxfish, all of which are from the highly derived order Tetraodonitformes. Their very large bodies could

be an adaption to lose heat slowly while foraging in deep waters. In fact, it has been found that larger sunfish are able to forage for longer periods of time.

Ok, so the large surface area helps the sunfish with thermal regulation. Fair enough. But how do you explain the evolution of those two giant fins (dorsal on top, anal on bottom) and the lack of a caudal fin? Surprisingly, the dorsal and anal fins actually work like wings to propel this animal to great depths, and at relatively high speeds. By stroking the anal and dorsal fin synchronously, they are able to generate a lift-based thrust similar to that of penguins. If a sunfish could brag, it would probably also tell you that they are the heaviest bony fish in the world, the most fecund vertebrate in the world (one female can produce 300 million eggs), and they are a host to at least 54 different kinds of parasites (their parasites… have parasites).

While a lot of advances have been made in learning about these uncanny fish, there is much more work to be done. With continued use of tracking and video equipment, the secret lives of sunfish will continue to be revealed… showing that they are not so lazy after all.

References:

For more information on the ocean sunfish and current research, visit the the Mola tag team website.